10 June 2020

Some five years ago, several protesters dragged an effigy, wrapped in a sheet splattered with fake blood to represent a corrupt government official across Poipet town. They wanted to voice opposition against their community’s eviction from their land to make space for a railway project.

One of them still feels the consequences of that protest today.

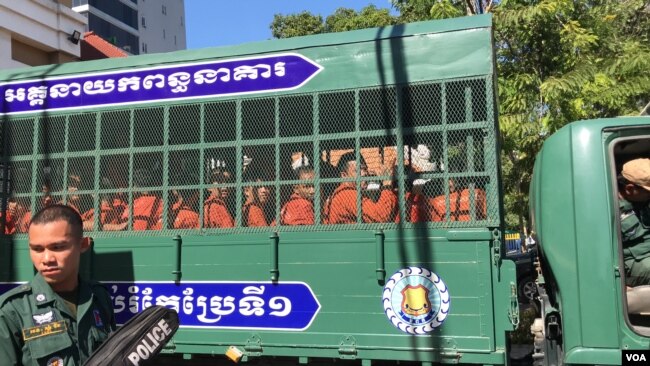

Activist Chheng Bunhak, one of the leaders of the protest, was arrested and charged with traffic obstruction and incitement to commit crimes.

But while he was released after two days following pressure by international and local rights groups, the investigative judge ordered him to appear at the police station in Poipet on the 25th day of each month. That condition still applies today.

Sitting in his home next to the railway in Poipet city, the 42-year-old said the court monitoring conditions have made his life difficult.

“At this point, I feel very angry because I don’t have the right to express my ideas since I am under the court monitoring,” Chheng Bunhak said, explaining that he couldn’t engage in activism for fear of being arrested again.

Aside from his activism, the court monitoring conditions also put him in a difficult financial situation. Before the court case, he would work in Thailand for three to four months, sometimes a year. And while he could only find work as an occasional motor-taxi driver or construction worker in Banteay Meanchey, where he would earn about $5 to $10 a day, he could earn a regular income between $9 and $12 a day in Thailand. With the court condition of having to reappear at the police station every month, he said he could not leave to work in Thailand.

At the moment, Bunhak said his situation was particularly difficult because there were no jobs available in the construction industry where he lives, and the coronavirus pandemic had slashed his already meager income.

“The [my] case should not be kept on hold like this,” he said. “For the last five years, I lost and wasted my time. I can’t go where I want to go. I lost my freedom.”

While maintaining his innocence, the former land activist said the provincial court should quickly put him on trial to clear out of the case.

“There should be an opening of what is called a trial to know whether I will be convicted or found guilty or what? The trial should be conducted,” he said. “ If I don’t fulfill [the court conditions], I will be summoned once again.

Bunhak’s pending case is among nearly 40,000 pending cases in Cambodia’s provincial and municipal courts, most of them related to criminal charges.

Purposeful Delays

Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director of Human Rights Watch, said the delay of cases was done on purpose. The courts, he said, acted on the whim of the ruling party and its ministers.

“The Cambodian authorities use some of these ‘old’ cases as a deterrent to prevent activists from protesting against human rights abuses or other forms of government malfeasance and corruption,” he said. “Basically, these cases are like the proverbial ‘Sword of Damocles’, left hanging over activists’ heads so they feel insecure and afraid that they could face trial and imprisonment at any time the government wants.”

Activist Din Puthy’s experience of the past four years mirrors this limitation. At the end of 2016, the activist’s case in Poipet city drew the ire of the media and observers when a border police officer in Poipet town ostensibly pretended to be hit by Puthy’s car and collapsed while the car was not moving.

Din Puthy, also known as Mang Puthy, was an official of the now-dissolved opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP). He was charged with intentional violence and sent to pre-trial detention after the accident.

Inside his home at Poipet, Puthy pulled out a stack of legal documents, neatly clipped together in one big folder.

Although he was released after three weeks in prison, he was only released on bail. His charges were never dropped, and he still has two other charges against him that he said stemmed from his human rights activism. One case, brought against him in 2009 remains pending.

Similarly to Bunhak, Puthy said he is struggling financially because of the court case. With three children to care for, he said the pending court case prevented him from getting a decently-paid job. For example, he said he had applied for a job at an insurance company but his application was rejected because of his open case status.

While selling gas and drinking-water in his small shop located in his house to make some income, he said some people refused to do business with him because they knew he had been charged with a crime.

Puthy believed that the courts kept the charges open on purpose to keep him from being an outspoken activist. To this day, he’s still the president of the worker association Informal Economy Reinforced Association, but he’s weighed down by the pending court cases. Because of this, Puthy said his advocacy activity has been weakened.

With charges never dropped, Puthy said it would be easy for the authorities to arrest him. “Authorities could issue arrest warrants if I’m engaged in advocating activities that they didn’t like,” he said.

The court cases also put him in a bad financial position, the travel to the provincial courthouse is expensive. “It’s difficult,” said Din Puthy.

But Chin Malin, spokesman for the Ministry of Justice, denied the allegations that courts purposefully delayed cases to intimidate activists. “[The activists] never acknowledge that they commit offenses that are against the law. When they caused chaos and the law is implemented, they said they are exercising their rights,” he said.

“For the authorities, they implement the law for all. They don’t care who the activists are… based on legal principles, nobody is ordering the courts to drop charges or to not drop them.”

Contrary to those claims, Long Sokunthy, 48, is another activist who feels the weight of pending cases and who believes that her case was not dealt fairly.

She was a representative for more than 200 families locked in a dispute over 1,400 hectares of land in O’Chrov district’s O’Beichoan commune. She spent 12 months in prison on allegations of destroying private property. Although the alleged crime happened between 2013 and 2015 according to the charges – she denies the charges – the arrest warrant was only issued in March 2018, a few days after which she was arrested.

But while she was released and is not technically under court supervision, she is still required to show up at court for a litany of charges. Of the 14 initial cases covering a period from 2014 until 2017, she still has to deal with 10. This means that she sometimes has to go to court three times a month. Most recently, she went to court at the end of May for allegedly having committed intentional violence in 2015. The verdict is due on June 15. Like in all other cases, she denies the allegations.

Costly Court Proceedings

Soum Chankea, a local representative of the right organization Adhoc in Banteay Meanchey province, said corruption made court visits costly.

“When our management is slow regarding documents and other issues, there always be … bribery and under-the-table fees. It’s been that the money will be spent at the court by the people whenever they go to court. If [you] want your cases proceeding to go quickly, let’s give [us] some money.”

While a lack of technical skills to handle cases digitally and limited human resources contributed to slower court systems, Chankea said some court officials created the backlog of cases on purpose by postponing trials of the accused to slow down the hearing process. He said some judges would postpone the trial on short notice even when the accused had traveled from long distance to attend the trial.

“But if the people didn’t come to attend the trial, judges will try them in absentia,” he added.

Long Sokunthy knows the consequences all too well. Sitting inside her small grocery stall, Sokunthy said she had lost her income and savings to the land dispute. Partially to pay for legal services, she took up a loan of about $10,000 at a microfinance institute. While she has cleared out her debts with that institute, she said she remained in debt with private lenders, including to family members.

Each time she went to court now she couldn’t spend time selling her groceries. Because she had to set aside most of her daily income to pay for her debt, she could only take away about $2.5 each day to pay for her food and other daily expenses – so going to court, she said, was a significant financial burden each time.

“I wasted my time on [these cases], while I am trying to do business,” Sokunthy said.

This also affects her mental health. “I almost lost my motivation to keep my business running and to continue living here,” she said. “We cannot concentrate anymore. [My] mind is in chaos.”

Like Bunhak, she wants to work in Thailand as a construction worker, but as long as the court cases are pending, she cannot leave. “I don’t want to live here, and I want to leave for good to Thailand,” she said.

Roeun Lina, spokesman for the Banteay Meanchey provincial court, declined to comment. Nguon Nara, president of the Banteay Meanchey Provincial Court, also could not be reached for comment.

Cleaning out Cases

Having faced years of criticism for its slow judiciary, the Ministry of Justice launched a campaign to reduce prison overcrowding and decrease the mountain of cases in May. It said it would do so by increasing the capacity at courts, accelerate trials, and increase the use of bail and suspended sentences.

Justice Minister Koeut Rith said the number of cases and inmates had increased on account of the government’s anti-drug campaign that started in 2017, which had resulted in an exponential increase in cases being sent to court.

The ministry did not provide details of how many cases were pending at each provincial court, though its statistics show that 12,000 are pending in Phnom Penh alone.

Phil Robertson, of Human Rights Watch, said the campaign should address long-term reforms to the justice and prison system. All unsubstantiated charges should be dropped, he said.

“The government should drop all the pending cases in which activists have been charged for simply exercising their rights to freedom of expression, peaceful public assembly, and other civil and political rights,” he wrote.

Echoing Robertson’s demands, Puthy said he would discuss with local rights groups to ask the Ministry of Justice to throw out his case.

“His Excellency Koeut Rith [justice minister] said he will clean up all the cases so that the cases will not stall [at the courts]. … if the cases are closed or charges are dropped, we would be happier because we are cleared from the cases, and we are not involved and our names are not at the courts anymore,” he said.

But Justice Ministry’s Chin Malin said the campaign aims at dealing with a general issue of judicial backlogs – it would not look into specific cases of activists.

“In this campaign, we will not separately look into specific cases or set focus on activists or the persons who are activists,” he said.

Yet, Bunhak has not given up hope that the campaign might clear him from the legal proceedings.

“What I want the most is the freedom to live as a dignified person like others because what they are doing every day is tying me up. I lost my freedom,” he said.